“When making a decision of minor importance, I have always found it advantageous to consider all the pros and cons.” – Sigmund Freud

In our last blog on 16th January 2025 entitled “Oil Prices: When does “complex” become “too complicated””, we discussed all the moving parts that contribute to the oil price negotiating process. We talked about the choice of the most appropriate published benchmark price to use in a contract price formula and how the price differential to the benchmark has to change if the composition of the benchmark changes.

In that blog we said if a counterparty to a contract suggests that any form of optionality in the delivery dates or the price averaging period should be inserted into the physical contract price formula, then we enter new and even more complex territory. The purpose of this blog is to consider that issue. Readers whose day job is not trading may find it helpful to read the previous blog before embarking on a consideration of the impact of optionality in the oil contract price formula.

One fact that the reader should keep front and centre in the mind is that the price of oil at any moment varies with its delivery date. The same barrel of oil can be worth simultaneously many dollars of difference in price depending on whether it is to be delivered next week, next month, or next quarter. This is not because oil prices are moving up and down all the time, although they are: it is because traders of oil will value identical oil at a higher or lower price today, depending on when it will be delivered.

Accordingly, the oil price formula in a contract will usually include a discount or premium to the chosen published benchmark price to reflect, among other things, any difference between the delivery date range of the cargo in question and the delivery date range considered by a price reporting agency (“PRA”) in assessing the benchmark price that the counterparties are using in their contract price formula. In other words, the contract should reflect any differences in the delivery date and pricing period of the contract oil compared with those of the published benchmark oil.

The Dated Brent benchmark assesses the value of oil for delivery 10-30 days forward from the PRA publication date. A typical physical crude oil contract price formula usually refers to PRA benchmark price assessments published, often, 5 days around or after the B/L date. Ergo, the contract formula is based on the price of oil to be delivered 10-30 days after the B/L date. This is a logical non-sequitur.

Originally the idea was that the value of crude oil should reflect the value of refined products extracted from the crude in a refinery and that those products would come to market roughly a couple of weeks after the crude oil was delivered to the refinery. That logic is now obscured by the mists of time. Suffice to say that a rational person attempting to understand why crude oil for delivery on B/L date, A, is priced by reference to published crude oil price assessments on or around the B/L date A, which in turn refers to oil for delivery 10-30 days after A, can be forgiven for some puzzlement.

For the sake of one’s sanity, it safest to just accept that this is a widely used convention that has evolved over time, but which does not stand up to close analysis.

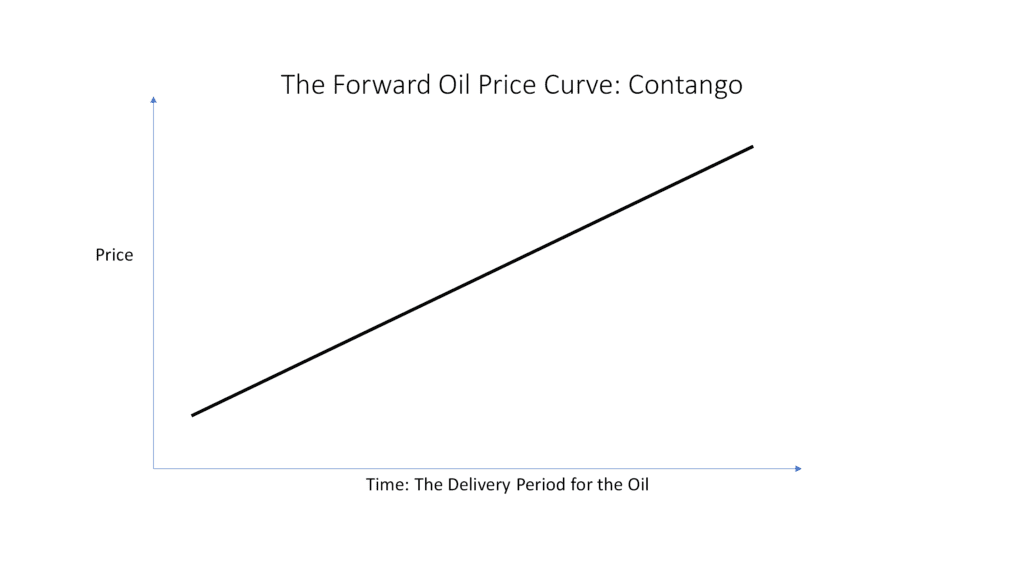

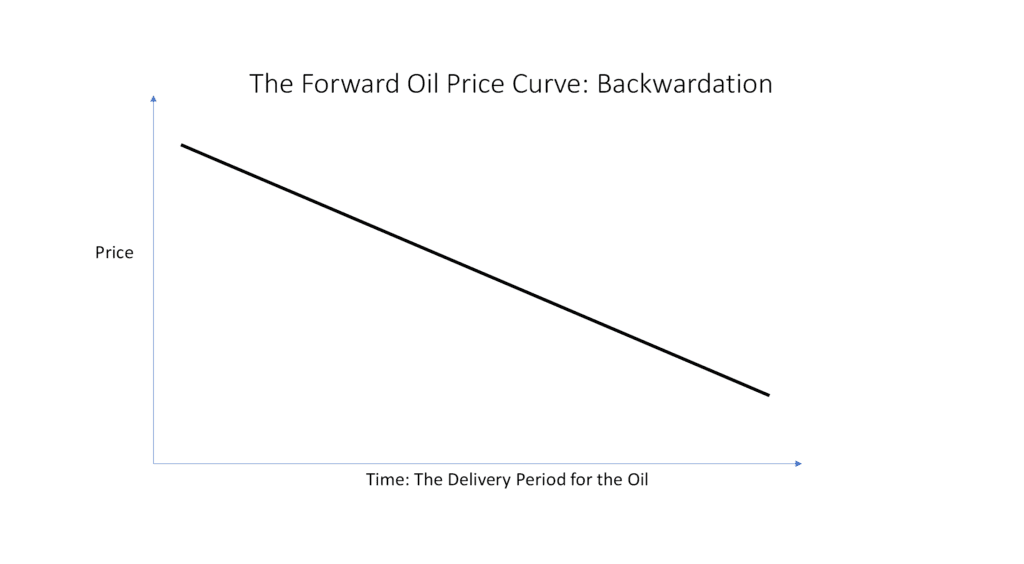

This concept is represented typically as a forward oil price curve, which is a graph showing the current market price, shown on the Y axis, for the same barrel to be delivered at various future points, shown on the X axis. The slope of the curve may be upward sloping from left to right (“contango”) or downward sloping from left to right (“backwardation”). This is illustrated in the Charts below. This is familiar territory to most oil executives.

In the first case, contango, oil for prompt delivery is less valuable at that point in time than oil for delivery in a later period.

Chart 1: Price Varies with the Delivery Date of the Oil- Contango

In the latter case, backwardation, oil for prompt delivery is more valuable at that point in time than oil for delivery in a later period.

Chart 2: Price Varies with the Delivery Date of the Oil- Backwardation

Both these charts represent a single point in time and what traders are prepared to pay at that point in time for oil to be delivered on different future delivery dates. It is not a price forecast.

The slope of the forward oil price curve can be referred to as the time differential (“T”) to distinguish it from the height of the forward oil price curve, the absolute price, determined by the benchmark price (“A”). The PRA publishing the benchmark price that the counterparties have chosen in their physical contract price formula, usually specifies the delivery date range it is assessing for a benchmark cargo. If the delivery date range of the physical cargo being negotiated is earlier or later than the PRA’s benchmark delivery date assumption, an adjustment in the contract price formula can be made in the form of a premium or discount to the benchmark price. This differential is derived from the slope of the forward oil price curve at the time of agreement.

The value of the time differential, T, can be fixed upfront by agreement by the counterparties to the deal, usually, but not always, at the time the physical oil sales contract is agreed. This may be expressed as:

The value of T, the time differential, like the benchmark price, A, is easily hedgable in the Brent market. In the case of the time differential, T, the hedging instruments available are the Dated-to-Paper contract for difference (“CFD”) market or the Dated-to-Frontline (“DFL”) markets.

Although “CFD” is a widely used term in the commodity markets simply meaning a swap, in the case of the oil market, CFD refers to the specific swap of a price differential between Dated Brent and, usually, the second contract month (“M2”) Forward Brent contract. These terms were explained in our blog of 16th January 2025.

A nascent CFD market for WTI FOB Houston based on 10-day average pricing contract periods has now emerged and is reported by the PRA, Argus.

The Brent CFD market is widely used internationally to set the value of T in physical oil contract price formulae, or to hedge the value of T when traders are locking in a margin between the purchase price and the sales price of cargoes of many different grades of oil across the world. The practice of rolling CFDs when trading companies hedge the value of T will be explained in the next blog.

It is not easy to understand that the “commodity” in question in a CFD trade is a just a price differential, which can be traded as easily as any other commodity. Once that concept is firmly fixed, the mechanics of the CFD market become quite straightforward. It is a simple swap. It establishes the traded value today of the time differential, T, the difference between the market price of oil for delivery 10-30 days forward from the publication date and the market price of oil for delivery at some future date, typically, but not exclusively, 2 months forward. CFD contracts in the oil market are usually arranged into separate contracts for weekly delivery periods up to 12 weeks forward.

Bearing in mind the link between the delivery date of a cargo and its price, we can now consider the main purpose of this blog, which is to consider how small producers or refiners may wish to respond to proposals by larger oil companies or traders to build some form of optionality into a physical oil contract price formula.

The sort of optionality we have in mind is, for example, when the buyer or seller of a cargo suggests that it should have the option to change the agreed delivery dates of a cargo or to shift the price averaging period of the benchmark price in the price formula.

It can be quite seductive if, say, the buyer proposes to pay the seller a better differential to the benchmark in return for the right to choose the delivery date or the benchmark price averaging period. This may be couched in terms such as, for example, the price will be the buyer’s choice between:

Obviously, a seller wants a formula that delivers the highest price possible, and the buyer wants a formula that delivers the lowest price possible. But how can anon-trading company decide in advance, sometimes even before the loading date range of the cargo is confirmed, if the extra $0.15/bbl is sufficient compensation for ceding the right to choose the published price averaging period in the contract formula, or even to choose the B/L date itself? The larger trading company probably a team valuing and hedging such options. The smaller industrial company probably does not.

Given the logistics of moving oil around the world in tankers, it is difficult to be certain in advance what the B/L date of any cargo will actually turn out to be. There may be loading or cargo documentation delays at a terminal. A ship may arrive early or late. The party in control of the tanker – the buyer in an FOB sale or the seller in a CFR, CIF or DAP sale- may decide to slow steam to ensure as late a B/L date as possible, or alternatively to order the “caps on backwards” speed to ensure as early a B/L date as possible. Because the ultimate price formula is calculated by reference to the B/L date, unsurprisingly there is a temptation to tweak the dates. This is particularly so around the month end when there may be a change in the host government’s Official Selling Price (“OSP”) for taxation, cost recovery and profit-sharing purposes between the months.

Often, to provide certainty and to facilitate hedging, the parties will “deem” the B/L date in advance. In other words, they set a likely B/L date and use that date in the contract price formula irrespective of what the actual B/L date turns out to be. It is not unusual for the party pushing for a deemed date to be the bigger of the two oil companies or the entrepreneurial trading company on one side of the deal. This is because such, more trading-orientated, companies will be considering a range of possible strategies for the cargo, which will require hedging their price risk to lock in the margin that they have identified in advance of loading, often at the time the deal is struck.

So, in summary, because the calculated outcome of the contract price formula varies with the B/L date, if the B/L date is a movable feast, it is difficult to hedge the price risk. Agreeing to “deem” the B/L date in advance of loading can help the more active trader to manage its risk because it sets the apparent B/L date in stone, irrespective of what it actually turns out to be.

Exactly how the larger and more trading-orientated counterparty of the two is probably arbitraging the cargo and earning a profit will be the subject of a subsequent blog. The trading company will typically be taking every decision with the forward oil price curve as a constant companion. This is less likely to be the case for a small exploration and production (“E&P”) company or a small refiner/consumer.

Typically, a small E&P company or a small oil refiner/ consumer has no interest in, or capability to pursue, the trading opportunities exploited by its larger counterparty. It may well have a completely different business model and make its money from activities in which the larger trader may have limited or no interest, such as finding oil with a drill bit or by upgrading and blending hydrocarbons in a refinery or storage tank.

Hence, it may make sense for the smaller company to sell the trading opportunities that the inclusion of optionality in the oil contract price formula represents. If a company is not going to exploit that optionality itself, it might as well sell it and get some value from having the option in the first place by virtue of owning oil production or owning a refinery or blending facility: the “use it or lose it” principle.

But a word of warning: the grantor, or seller, of the right to choose should be aware of the tax reference price(“TRP”) or Official Selling Price (“OSP”) it will face when it reports to the relevant Tax Revenue Authorities or government custodian of the Production Sharing Contract or Service agreement. This may be based on the actual B/L date and the taxation or other government authority may not recognise the deemed B/L date that sets the physical contract price. This will give the option grantor hidden basis risk.

Buying an option of any kind in a commodity or financial instrument is a risk-reducing activity. Selling an option is a risk-increasing activity. So, if a small producer or refiner grants, or sells, the option to choose the delivery date or the price averaging period in the oil contract price formula, it is advisable to have a good understanding of the risk it is taking on and the value of that risk, or option, in the market.

The value of the option to choose, or deem, the B/L date and/or the benchmark price averaging is straightforward Options 101. The value of any choice, or option, is determined by:

Options traders have a mathematically complex model that allows them to calculate the price of an option, referred to as the options premium, based on variations of the Black Scholes options valuation model. The variables listed above are variables in the Black Scholes model.

There are three basic types of option, which have a range of different labels in different commodities and in different areas of the world. For the purposes of this blog, we will use:

In the case of oil, usually contracts between a non-trading firm and an oil major or trading company involve Asian style options. This is because, in such contracts, the price formula is usually an average of benchmark prices published over a number of days, rather than a single number, $X/bbl.

It may not be immediately obvious how these concepts apply in the case of granting an option to deem the delivery date or choose the contract formula price averaging period, but they do.

For the purpose of this blog, to value what the right to choose or change the B/L date or the price averaging period, a bit of imagination is needed. It needs the reader to put themselves in the shoes of the option seller without its own trading department.

The strike price of any option may be identified as the price that the recipient of the option is acquiring the right to choose. If that strike price is more favourable than the current market price then the option is said to have intrinsic value, or to be “in-the-money”. It has a positive value. The opposite case is when the strike price is less favourable than the current market price and the option is “out-of-the-money”. It has no intrinsic value.

These terms mean simply that if you were to exercise the option now would you be making or losing money. If an option is losing money, it will not be exercised and will expire worthless. Alternatively, it may be sold in the market to recover that part of the option value that is not associated with the difference between the strike price and the current market price, as described above.

In the context of this blog, consider the strike price to be the right to choose alternative contract price formulae that the grantor, or giver or seller, of the option is giving its counterparty. Whether the option can be said to be in or out-of-the- money will depend on a comparison of the strike price formula compared with the current benchmark market price of the “correct” price formula for the cargo in question. This is where it gets interesting. What is the “correct” benchmark price averaging period of any cargo?

As we said in our previous blog of 16th January 2025, Platts assumes that, in the case of North Sea grades, contract price formulae often use the 5-day average of published prices around the B/L date for physical oil, with the B/L date being the mid-point of the price averaging period. This is so-called “2-1-2” pricing. In the case of West African grades, the norm is to use the 5-day average of published prices after the B/L.

Not all actual deals done in the market are transacted on a 5-day average period, particularly in the case of refined products. This is just what Platts assumes in assessing oil prices for publication purposes. Some deals are done on a whole month average (“WMA”) price, with the month being determined either by the actual B/L date, a deemed B/L date or the date of the Notice of Readiness (“NOR”) to load or discharge the cargo. Others are done on a balance of month average (“BALMO”).

So, when it comes to evaluating the intrinsic value of an option to choose the contract formula price averaging period or to deem the B/L date, what is the correct benchmark price averaging period of any cargo? This is what will take on the role of “market price” in establishing the intrinsic value of the option in our analogy.

The practical answer is that the de facto market price is whatever the grantor of the option wants it to be. If the smaller company wants 2-1-2 pricing that is the de facto market price. If the larger company wants the option to choose the average of published prices published on the 10 days after the deemed B/L date that becomes the de facto strike price.

So to be clear, if, say, a small producer enters into a term contract to sell its oil it might prefer that for each cargo delivered under the terms of a long-term contract the formula contract price will be based on, for example, the WMA of published benchmark prices over the month in which the B/L date of each cargo falls, either actual or deemed. That can be considered to be the market price for option evaluation purposes in the context we are considering in this blog. If the counterparty would like to option to choose a different price averaging period or deemed B/L date, that alternative price becomes, in effect, the strike price of the option.

From the perspective of the larger, trader-orientated company, the option can be considered by reference to the forward oil price curve and the CFD market. This will be discussed in our next blog.

From the perspective of the smaller producer or refiner, the forward oil price curve may be unfamiliar territory and too remote to assist in working out the ex-ante value of giving away the choice of B/L date or price averaging period. Such companies, understandably, often value the option ex-post. In other words, they are only concerned with the price in $/bbl that emerges on the invoice after the prices for the contract price formula chosen by the larger company have been published by the PRA.

When the contract is being negotiated, the smaller, less trading-savvy, company may evaluate the option by looking at what price the various alternative contract formulae would have delivered historically. This will suggest a completely different option value than the one available to the larger, more trading-orientated, company derived from consulting the forward oil price curve and their option valuation model at the time of the contract negotiation.

This is a fundamental philosophical difference in approach between small “industrial” firms without their own trading department and large oil and trading companies.

As mentioned above, we will consider the traders’ approach to this issue in our next blog. But the ensuing discussion looks at the issue from the perspective of a small E&P or refining company wanting respectively the highest or lowest price possible.

In attempting to illustrate the issues associated with optionality we have considered actual prices during a typical historic 3-year period, Year 1 (“Y1”), Year 2 (“Y2”) and Year 3 (“Y3”).

Suppose that in October of Y2, a small E&P company was lining up a contract to sell 1 cargo per month in the following year, Y3. Having agreed which benchmark to apply, the E&P company has to decide which price averaging period it will agree with a buyer to use for each cargo in all the months of the delivery year, Y3.

One starting point might be to look at what the various likely price averaging periods might have delivered in the previous two years, Y1 and Y2. [Note: At this point in the narrative, we are only considering the benchmark price averaging period for A, not the time differential, T, or the grade differential, G.]

In October Y2 an analysis of the previous Y1 and year- to -date Y2 would show that, compared with a fixed index, with hindsight we can say that the 5 after B/L price averaging period could potentially have yielded the highest price on average for each month and that the 2-1-2 price averaging period could have yielded the lowest price (See Table One).

The price outcome from different price averaging periods depends on the actual or deemed B/L date of each cargo delivered each month. Hence there is actually a Min-Max range of outcomes for each price averaging period.

Table One: Historic Analysis of Price Averaging Periods

It is evident from Table One above that the range of possible price outcomes from different price averaging periods not only depends on the actual or deemed B/L date but that it may be measured in dollars, not just a few cents. This should be borne in mind when selling the option to choose the price averaging period or the B/L date.

The small E&P company seller, in the absence of information concerning the forward oil price curve in October Y2, might have decided to take the middle road and go for whole month average, WMA, pricing. This would eliminate the range of different possible outcomes for each price averaging period arising from the movable B/L date. It would also iron out the peaks and troughs in the market value of benchmark price, A, applying to its possibly sole cargo each month. This becomes the seller’s preferred market price for the purpose of the option valuation discussion.

Had the E&P seller chosen WMA pricing, by looking back when it got to the end of Y3 it is apparent that the absolute price, A, had fallen substantially. Choosing the WMA pricing period would have delivered an average price outcome in the middle of the range of possible average price results.

That is all that this form of historic analysis reveals. It is an inadequate basis on which to choose the “best” price averaging period going forward, other than possibly leaning towards as long a price averaging period as possible.

The forward oil price curve in October Y2 would have shown the price, in October Y2, at which oil could be sold for delivery in each of the months of Y3. The E&P company could then have chosen to lock in the forward oil price curve value of A, the benchmark, by hedging.

Small consumers and E&P companies do not always consult the forward oil price curve or have the financial capacity, or board delegated authority, to hedge. Unless a company decides to act on the forward oil price curve now by hedging, today’s curve becomes no more than the white noise in the market, and it will have changed by tomorrow.

The forward oil price curve is the territory in which larger oil companies or trading companies mine for profits. As mentioned above, the traders’ approach will be explored in the next blog. Suffice to say for the purpose of this blog that the profit opportunities enjoyed by trading companies will often prompt them to seek the option to choose from two or more price averaging periods or deemed B/L dates in a sale and purchase agreement with a non-trading company. These alternative pricing and deemed delivery date proposals are analogous to different option strike prices to the non-trading company.

If the non-trading company is not in the position to exploit such profit opportunities, it makes considerable sense to sell this flexibility to someone who can. But at what price should the option to choose from two or more price averaging periods or deemed B/L dates, be sold? That depends on when the option has to be exercised and how long the buyer of the option has to decide which of the alternatives to choose. This is the option’s time to expiry.

The time element of option valuation refers to how long the buyer of the option is given to decide whether or not to exercise the option before it expires. The more decision time allowed until expiry and the nearer is the expiry date to the contract price averaging period, the more expensive the option. This is because the longer the option buyer has to decide the more likely it is that natural market price movements will put the option in-the-money. The nearer is the exercise expiry to the beginning of the price averaging period, the more data the holder of the option has to inform its choice.

Ideally, from the seller’s viewpoint, the option should expire just before the price discovery period starts. So, if the option is to choose between, say, 2-1-2 pricing and 5 after B/L pricing, the option might best expire 3 days before the B/L date, when no information is yet available on what price of benchmark, A, will be published for each of the dates in question. Similarly for WMA pricing for month, M, the option expiry might best be set at the last day of M-1.

But the less time the option buyer is allowed, the less valuable the option and the less the option buyer will be prepared to pay. This is a risk/reward trade-off for the option seller.

It is becoming increasingly common for traders to seek “look back” options, i.e., the right to choose the price averaging period or the deemed B/L after all the relevant prices have been published. This is equivalent to having the right to choose heads or tails after the coin has landed. So, the option buyer, logically, will always choose the price most favourable to itself each month, to the detriment of the option grantor. It will never act in favour of the option grantor.

Traders or large oil companies may well offer seemingly attractive price differentials to have a look back option, perhaps $0.50/bbl or more. But a quick recap of Table one above indicates that a look back option can cost the option seller many dollars of lost revenue, or opportunity cost, on average each month.

The actual impact of the look back option is to give the seller the least favourable price on each possible B/L date, not just on average each month, so the opportunity cost can be much greater than the monthly average price implies.

The option grantor may decide to agree to a look back option anyway, gambling that the market will be calm and the difference between the highest and lowest possible price outcomes that it is foregoing will be less than the gain it makes from the better price differential in its sale and purchase contract for the oil. The more volatile is the market, the greater the gamble.

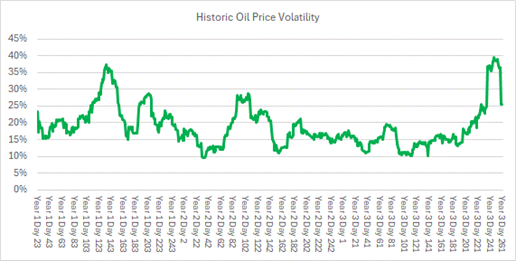

Volatility is one of the variables that options traders consider when valuing the price of an option. The more volatile is the market the more likely it is that the option will become “in-the-money” even for a short period of time and allow the option holder, or buyer, to exercise it, or sell it, at a profit.

When there is an event or an announcement that has an impact in the price of oil there can be a sharp spike in volatility, triggering the exercise, or sale, of some options which have come into the money.

This is not a variable that has much meaning in a quantitative sense to a non-trading company, but it is of some relevance in the eyes of a trader. Even companies without an active trading department can observe whether or not the oil price has been volatile recently and judge subjectively if such volatility is likely to persist in the future. High volatility is unlikely to act in favour of the option seller, unless they can extract a higher premium from the option buyer.

Chart 3: Historic Oil Price Volatility

In basic economics, all investments are measured against the risk-free alternative, i.e., instead of writing an option, the option seller could put its money in the bank and earn interest. The higher the interest rate, the more an option grantor will want to compensate it for the risk of granting an option. So, the higher the interest rate, the higher the option premium.

Again, this is not a variable that is likely to enter into the thinking of a small E&P or refining company when deciding whether or not to allow the larger trading-orientated company the right to choose the price averaging period or the deemed B/L date in a sale and purchase contract.

Implied volatility can be described as the level of volatility required to generate the option premium that is actually being traded in the market. Given a known market price for the underlying oil, a known option strike price, expiration date, historic market volatility and interest rate, the Black Scholes model may suggest a certain ”scientific” option premium. But if the same option is actually trading in the market at a different option premium, the difference can be referred to as “implied volatility”. It is shorthand for all the other factors that have an influence on the price of the option. This simple description annoys the bejeezus out of pure options traders.

Implied Volatility is most likely to be heavily influenced by the bargaining strength of the two counterparties to the physical oil sale and purchase agreement and how much of the “economic rent” the buyer of the option is prepared to share with the seller of the option. It will be shaped by the number of other parties in the market competing to take the other side of the smaller company’s deal.

It would be naïve to expect that the foregoing analysis would be of much assistance to a non-trading company attempting to put an objectively” correct” price for giving away the right to deem the B/L or to choose the price averaging period. However, there are several messages to take away from this blog:

It should be understood that as between the two counterparties to the physical sale and purchase agreement, the size of the option premium is a zero-sum game. However, the more active trading company is unlikely to be just buying the option to set the B/L date and the price averaging period and leaving it at that. It is likely that the cargo in question will form just one component of an arbitrage jigsaw puzzle, which will involve, in all probability, a number of financial and operational risks that must be hedged.

Although industrial firms without a trading department might not be in a position to enjoy the profit opportunities available to a trading company, before agreeing a price to give them away, it would be helpful to understand the profit prospects available to active traders.

That will be the subject of our next blog.

Hindsight is no guide to the future.

“The farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.” ― Winston Churchill

Sorry, Winston, I disagree. Not if someone rearranges the landscape with tariffs, sanctions, production shutdowns, wars or some other fundamental game-changer.

I prefer: “The future is an undiscovered country”- Klingon Chancellor Gorkon (with apologies to Hamlet)

Liz Bossley, with thanks to David Povey and Ben Holt for their help in peer reviewing this blog.